Lecture Performance by Thiago Hersan

Thiago Hersan, Emily Hsiang-Yun Huang, and Daniela Ruiz Moreno

The lecture performance is commissioned by Project Embodied Interface and the Article is published in collaboration with SCREEN

Embodied Interface (E.I.) is a project that articulates research, creation and discussion around network art through Asia, Latin America and Europe. With the support of the National Art and Culture Foundation from Taiwan, in 2021, Embodied Interface had its first public session. Other Networks, Other Intimacies was presented as a lecture performance by Thiago Hersan within the Embodied Interface webinar in January 2021.

Introduction

Given the complexities of our hybrid and hyper-connected world, it is necessary to rethink how we want to connect, create and live within networks. In a world where a virus is not just a biological issue, it is impossible to try to understand our situation without recognizing the networks and signals that cross and connect us. We are part of invisible systems whose signals permeate and reverberate within us, but our lack of sensitivity to them makes us even more passive within these networks.

In this talk Thiago will present some of his projects that have been motivated by a desire for more personal and affective uses of networks.

In a world where humans/non-humans, nature/culture, bodies/machines, subjects/objects are all actors on the same networks, we need to learn to guide ourselves “by the pleasure in the confusion of boundaries and the responsibility in creating these temporary, provisional, problematic connections” (Haraway).

Transcript of Thiago's Performance

This work is about networks and intimacies, and intimacies on networks but before passing to projects that focus specifically on that, I want to present other projects to offer some context.

[img. 1]

[img. 2]

Does anybody know what this is? [img. 1] or this? [img. 2] That's what is inside of micro chips or integrated circuits. [img. 3] That’s what I did, that's what I studied in University and that’s what I worked on after I graduated. I was a circuit designer for a couple of years. What was interesting about studying this is that when I started studying computer engineering and computer science, the Internet looked like this [img 4 and 5.] but in our head it felt like a wide open space of exploration, of learning, of building, of meeting people. It was a time when using the Internet and programming the Internet was pretty much the same. But, by the time I finished studying, a lot of the Internet looked predetermined, with predetermined forms, predetermined questions and with reasons behind all this. And besides being boring, it was kind of a disappointment.

[img. 3]

[img. 4]

[img. 5]

So, some of the projects which I am going to talk about were initially motivated by this tension of what a network like the Internet could have been and what it becomes once it grows the way it has.

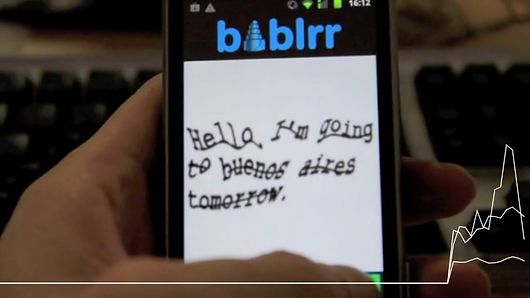

[img. 6]

A first project motivated by a desire to continue using the networks in a more personal or affective way was called bablrr which is an android app. What this app did was turn text into purposely distorted images of text [img. 6] like the captchas the websites use to make sure that you are a human. So you write a little message, it generates an image of that message and the idea is that if you use this image on email or social media, the algorithms can't read this, because the point of the captcha is that only humans can read them.

An interesting thing about this project is that a couple of years ago I went on the Google Market App site to look at stats and it has been downloaded mostly in the US, in Brazil, in India which makes sense but also in Irak, which I don’t know why.

[img. 7]

[img. 8]

Another project along similar lines is I like you (on Facebook) which explores the idea of what is love if not the sum of all likes. What this app or script does is that when you go to this website and you log into Facebook you see a list of all your friends and when you select one, the app goes through and likes everything that the person has ever said, every image that they are on, every text that they are tagged on. And while it does that you sit there and wait and you see the script progressing. [img. 7 and 8 ] Of course I got kicked out of Facebook for this, they don’t want to do that, they much rather know what you really like or don't like, they don't want you to mess up their algorithms. They let me back in later. Eventually they also changed how these apps are programmed so something like this is not possible today, you don’t have access to other people like bottoms in an automated way like this anymore.

In a way this is a project where I try to play with the limits of what these websites or these Internet give us now. I try to push on them a little bit. If I can do something outside the Internet, why can’t I do it on the Internet?

[img. 9]

Another thing that happened around the same time I was doing these projects is that I met other people who had similar questions and anxieties about the Internet as we knew it. So together we formed a collective called Astrovandalistas. What we wanted to do initially in our projects was to create new input or output interfaces for the networks that we already used, such as SMS networks, phone networks or the Internet. So the project that best exemplifies this was Arma Sonora Telemática. This was our attempt to transform virtual digital protests into something physical and analog. We participated in an event at a culture center that was across the street from an army base and at the time the army base was the target of complaints and protests including some very popular hashtags on Twitter. So we modified the structure that we found near this army base and included metal curtains around the other metal structure and attached them to a washing machine motor. [img. 9] So every time a protest hashtag appeared on Twitter, every time it was used on a tweet, the motor was activated and the structure banged, making a lot of noise. This was our way of extending the interfaces that are given to us by these networks and create something a little bit more affective or personal and meaningful.

[img. 10]

[img. 11]

We also did other projects that you can check in our website (https://astrovandalistas.cc/) but around those years some things happened, one of them was Snowden. We already knew this or suspected but this guy really showed us exactly the depth of the entanglement between these companies and governments and spy agencies. And at the same time, pop culture was promoting this idea of the cloud as this weightless thing that hovers above us and just shines down happiness. While in reality the Internet is very much physical. This is a map of underwater cables that connects different countries [img.10] and this is part of the infrastructure of the Internet, this is what a cross section of one of these cables looks like. The Internet is nothing but other people's computers. This is a picture of a data center, each shelf has 10 to 15 hard drives. [img. 11] And this is more of the infrastructure that is needed to keep this running, this is probably to distribute energy or water to cool down the circuits. [img. 12] So given the size, the magnitude, the materiality of these networks and these companies, both within the collective and personally beyond the collective, we were coming to terms with the limits of using other people's networks.

[img. 12]

Imaginario Inverso: When we learned that the Nasa has a couple of projects where they use lasers to transmit data across large distances, of course we wanted to make our own laser modems to transmit data and in this way create our own infrastructure for different kinds of networks. And when we were invited to participate in an exhibition along the border between Mexico and the US, in El Paso and Juarez, we wanted to build a couple of these laser modems and distribute them among the region, so that people would have their private networks to transfer data. And we did that, we built prototypes for these transmission and reception circuits and they transfer information for about 800 meters at dial-up modem speeds. But while we were there and working with different groups that wanted to be part of this network, we realized that this kind of data transmission was not that important or necessary for these groups involved, and that transmitting short messages across the border is pretty easy with the technology that is present there. So we noticed that actually what was important for the people of the groups we were working with was a kind of communication with the future or a kind of communication that has more duration, that lasts for longer periods of time. So also using lasers but a different kind of laser, we modified a laser-cutting machine and we created an interface to turn text messages into images, so that messages can be written on rocks and then transferred across the border. [img. 13 and 14] Through some workshops with the groups we came up with short predictions for the future or short phrases that express their worries for the future and engraved those into rocks that can be traded across the border. While the rocks do contain text messages that can be decoded and understood, the real network here was created between the people involved who had to coordinate between themselves, to exchange the rocks and transfer them to one side of the border to the other and make them go where they wanted them to go.

[img. 13]

[img. 14]

Antenna jewelry: While looking at space and stars, this project made me personally want to start to look at other kinds of technological networks and communication networks that are already around us. So I started researching satellites and different types of electromagnetic transmissions and this is a representation of all of the satellites that orbit the Earth and this is a graph of all the signals that I receive in my house, between 100 MHz and 2500 MHz. [img. 15]

[img. 15]

So I set up a little antenna, a little receiver in my room and picked up random signals for a couple of minutes and I can see where the more popular ones are, like FM, TV, GSM, 3G, WiFi. One thing that the variety of signals made me think about is that each one of these frequencies would require a very specifically sized and shaped antenna to receive and transmit that signal. So this is physical negotiation where metals of specific sizes resonate at specific frequencies. In a curiosity about what kind of signals would my body be sensitive to if I considered my fingers as antennas, I started making a collection of wearable antennas, a kind of jewelry where the pieces of metals on this jewelry are based on the sizes and shapes of my finger joints. [img. 16 and 17]

[img. 16]

[img. 17]

By making these antenna jewelry pieces which are based on my finger sizes, I am doing two things: one, trying to measure the types of signals that my fingers are sensitive to. And second, if someone else wears this, it can create a kind of symbolic connection where they also become sensitive to the signals that my fingers are sensitive to. And so for example after connecting this to a circuit and doing some measurements, I can see that this one is sensitive to 1400 and 1970 MHz. And this other has sensitivity peaks 790 and 1300 MHz.

[img. 18]

Pyramids: While the antenna jewelry is a way to make sense of some of the signals that we swim in. One part of the spectrum is very much known to us and very much utilized everyday, and that's the 2.4 GHz part of the spectrum where a lot of our WiFi signals will be transmitted. In an attempt to occupy that space or to connect to the signals that are already inside that space I started making these objects. [img. 18] So each one of these pyramids has a receiver and transmitter circuit and each one of these circuits are also programmed with a different type of algorithm. Overall what these pyramids do is that they listen to specific channels of WiFi and they capture their data being transmitted, and then re-transmit it using their own logic. They don’t affect the transmissions that are already happening, they don’t hack anything, they don’t decrypt anything, they just capture the 0 and 1 that are floating around them and then they re-organize these 0 and 1 using their specific algorithms that they are programmed with. In a way it is like a purification of the WiFi space, so they transmit a more organized stream of 0 and 1 on top of the disorganized multitude of 0 and 1 that are floating around them. These are little visualizer screens [img. 19]. The white one is the original signals on some given WiFi channel, the red one is one of the pyramids retransmission after organizing it, and the blue organizes the data that it receives in an increasing or decreasing order before it retransmits it. These are visualizers for what the pyramids either receive or transmit.

[img. 19]

And as I finish these objects, my original intent was to set up a pop up shop somewhere and sell them in a kind of performative way where I do readings with the person that wants to buy one of them and try to figure out what’s the best antenna ring for them or the best algorithm pyramid for them. But given the current pandemic situation I am not able to do that in person so I set up a website (https://outras.ml/ ) to sell these objects.

[img. 20]

The prices for each of these objects in the website is dynamic, the object itself helps to determine its own price. So if a pyramid is not seeing the signals that it wants to see or it has poor reception, or if an antenna ring is not seeing the signal of which it is more sensitive to, their prices will drop. Almost as a way to show their desire that they have to go somewhere else. And besides the objects themselves, my body also determines their prices, given the pandemic context in which this was created, the prices are also affected by my body temperature and my heart beat rate. In case I get a fever or when I become more anxious and my heartbeat goes up, that drives the prices of the objects up as well.

[img. 21]

So this is what this jewelry is, it actually holds the heart beat sensor on my finger tip and I have a temperature sensor under my arm, [img. 20] and the graphs that you are seeing on the screen, one corresponds to my heartbeat, another to my temperature and another is WiFi channel 1 signals. [img. 21] And then on the websites you can see the history of the prices of each object. My plan for this website is to actually expand and invite other artists to showcase other objects or products as long as they also are willing to connect their bodies to the prizing system of the website.

To me these projects are a way to explore or become more sensitive to these hybrid networks that we are part of. And they present ways for us to start to try to resensitize ourselves to the different signals and the different actors that are part of these networks.

In a world where a virus is not just a biological issue, but also an economic, a political, a social issue, it is important for us to try to understand and become more aware of the different networks that we are part of, and at the same time its just as important to come up with new ways to connect to these networks or to responsibly create new networks where we can more meaningfully participate.

---

Embodied Interface (E.I.) is a project that articulates research, creation and discussion around network art through Asia, Latin America and Europe. With the support of the National Art and Culture Foundation from Taiwan, in 2021, Embodied Interface had its first public session.

E.I. had the multiple aim to review an earlier stage of the history of art developed with and by the influence of the advent of network technologies, but as well to feature contemporary artists whose practices explore different relationships between the physical body, the production and the consumption of network technologies.

Participant artists: Ronald Bal (NL), Vuk Cosik (SI), Thiago Hersan (BR), Yuki Kobayashi (JP), Brian Mackern (UY)

Curators and research team: X.Y. Huang (TW), Rok Kranjc (SI), Daniela Ruiz Moreno (AR)